In pursuit of self-sufficiency, Ibrahim Salah has invited his community to journey with him as he learns how to grow and prepare food that nourishes the body and the soul.

“Growing up in my area, where I went to school, what was available for me to eat, I realised that food is a big thing,” says Ibrahim Salah. “Food is used for survival, nourishment. Without food, you wouldn’t survive. Food is crucial for life. There’s something deeper about food, the impact it has on you. Good food will bring about a more positive feeling in comparison to food that isn’t nutritious. I don’t say ‘bad food’ because food is used for people to survive, you know? I don’t want to disrespect it.”

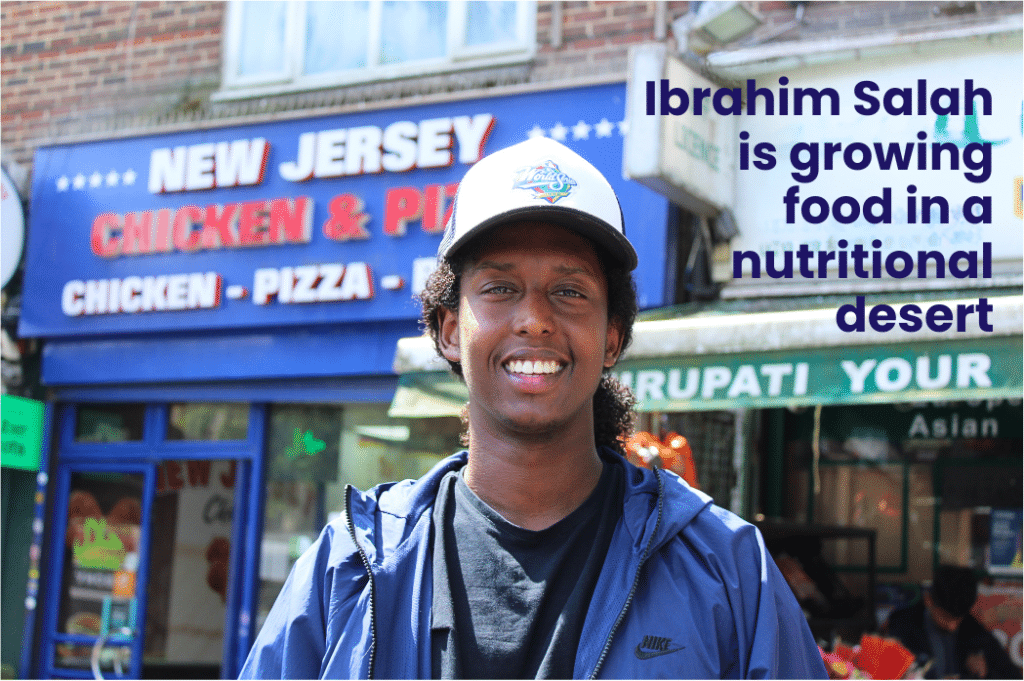

Ibrahim lingers familiarly outside Bambino Chicken, which stands as tall as the neighbouring entrance to Burnt Oak underground station in Northwest London. Bambino Chicken was an enduring feature of Ibrahim’s childhood and, for many years, he ate there after school.

“Chicken and chips was a big part of my diet, the reasons being that it’s delicious and the accessibility,” says Ibrahim. “How come on one road you have five or six different chicken shops? As we look around the area, you do have a lot of fruit and veg available, but it’s not available the way hot food is available in chicken and chip shops where the meal is ready straight away. Whereas with the fruit and veg, you’d have to divide your money in a way that you see fit and buy the right ingredients to actually cook a good meal out of it. If you’ve got a few coins on you, you can just go to the chicken shop, get a burger and chips and a fizzy drink and you’ll be filled up for the next few hours.”

On the busy avenue running through Burnt Oak, several colourful greengrocers advertise single portions of fruit and vegetables that cost more than a substantial meal at the numerous chicken shops nearby. The adjoining estate in which Ibrahim spent much of his childhood, Grahame Park, offers little better access to affordable and nutritious food.

“Grahame Park is a big part of my life,” says Ibrahim. “It’s an estate and you can see it’s a bit deserted. There’s a concept called a food desert and it basically means not having access to nutritional foods nearby. An estate like Grahame Park is massive, and you’ve got two convenience stores serving a few thousand people on that estate. You’ve got a chicken shop and a Chinese shop that sells fried food and deep fried chips at a cheap price but if you do want to go shopping, you’d have to go to either Burnt Oak by bus or travel all the way to Colindale Asda which takes you about fifteen minutes by bus or thirty five minutes if you’re walking. If you don’t have the luxury of a car, you have to be mindful of how much you can carry back home.”

Edgware, Burnt Oak, Grahame Park and Colindale all exhibit glaring wealth disparities; not least in the form of housing developments, but Ibrahim explains that much of what one might see on walking through these areas is an illusion. The modern building facades conceal less pleasing living conditions and, like the plush greengrocers scattered throughout these areas, give the illusion of abundance where deprivation is the more common experience.

“In my household, it was important for my mum to be within budget,” says Ibrahim. “If she’s buying things, it’s to see which has the most impact in terms of value for money, so it’s all about filling the belly at the budget we had. Sometimes, as much as my mum tried to eat fruits and veg, a lot of times it was canned foods and it’s no fault of my mum’s. I knew the way she grew up back home, a lot of the foods were organic, but that same food here might be too expensive so probably priced out. As a culture, we’ve adopted fast food as a quick fix. Being able to buy children what they want and spending two pounds on two burgers and two chips, you’re laughing to the bank.”

“Before I could change people, I had to change myself.”

When he was a teenager, Ibrahim began noticing the impact that consuming deep fried foods on a daily basis was having on his focus at school. He says that, while the fast food made him feel full, he was struggling to concentrate throughout lessons and often felt lethargic.

“Before I could change people, I had to change myself first,” he says. “I’m twenty-six now but I remember at age eighteen I made the conscious decision that I’m going to stop eating food like chicken and chips, fried foods, and adopt a more healthy lifestyle. I started experimenting with fruits, investing my energy, my money and my time towards that. I learned about the benefit of eating different foods and had a paradigm shift. My whole lifestyle changed. It was an eight year long journey to find myself and become that change that I felt like is needed in my community. I don’t want to be a hypocrite as well. I can’t be telling people, you need to do this and that. Obviously, throughout the years, I’m not saying I haven’t eaten chicken and chips but I don’t even enjoy it. If anything, it hurts my stomach and I’m not used to that type of food anymore.”

Another new habit that Ibrahim implemented during this period was taking regular walks in natural spaces, during which he made some important observations about why he and his friends had not often exercised in the local park.

“Going for nature walks might seem simple but I would never have seen myself before, as a young teenager, being into that sort of lifestyle, getting my friends to come out more. If you actually go into the park, the people you see are not working class people. A lot of the time they’re middle class people because they have the access and knowledge and they understand what’s good for them, like how a short walk in nature can change your mood, clear your head. But for us, we might just resort to smoking weed or do things that make us feel worse. A lot of that comes from knowledge.

Access to knowledge was a big part of why I applied to the Challenge and Change Fund; space was another reason as well. Being here in London, especially Northwest London, we’re fortunate to have a lot of greenery and we have spaces that I used to walk past everyday. There’s a few allotments in this area, places me and my friends stood outside not even realising what’s happening in them. The first time I went to an allotment, I thought ‘wow, we actually have places like this nearby that are almost like a farm where you can grow things in your own area.’ I realised that people who have access to these spaces are not people like me or my family and friends. They might have heard of the term, ‘allotment’, but they don’t know there’s one right there. I learned that there’s a waiting list, some waiting lists being seven to ten years long, and a lot of the people who have spaces in these allotments are well off and had that knowledge from early on. I wanted to relay everything that I learned so everyone in my area was more aware.”

“Me planting that seed, nourishing it and allowing it to grow has a long lasting impact. It’s given me a lifelong purpose.”

With support from the Fund, Ibrahim has built a project through which he is empowering local low income families to become self-sufficient and grow their own food.

“It’s important to understand how to grow food and to make places where you can do that accessible,” explains Ibrahim. “So far, I’ve organised several allotment days on Saturdays where we learn about planting, weeding, flipping beds and different techniques, we actually get our hands dirty. A lot of people have never had any experience in gardening and growing food or even being in an allotment.

The people I’ve brought together range from eighteen to twenty-six, people from different backgrounds, people I consider like myself from low income families to those that are in comfortable positions, so it was nice to have a variety of people coming together. We might cross each other on the pavement but there’s not many opportunities where we sit down together and eat some nice food and actually talk about where we’re from and understand each other better. Turnout is variable, sometimes three people attend, sometimes seven or eight, but big respect to the people who only come for one session for getting out and pushing themselves.”

Ibrahim has taken the group to visit and learn skills at allotments in Tottenham, Manor House and Finsbury Park. He frequently organises nature walks for young people in areas where there is a minimal risk of negative interactions between people; a critical intervention in an area where two of Ibrahim’s young friends were recently stabbed to death in public spaces. He has also taken groups of young people to visit the Welsh Harp nature reserve on the border between Brent and Barnet.

“There’s an estate there and I wanted to create a sense of ownership and pride,” says Ibrahim. “So I dedicated Sundays to litter picking, starting with a check-in and then going for a walk, becoming more familiar with spaces around the corner. I try to keep it light, fresh, interactive.

I didn’t realise how much everyone would enjoy this project. It opened their eyes. Me planting that seed, nourishing it and allowing it to grow has a long lasting impact. For myself, it’s had a massive impact. It’s given me a lifelong purpose that I want to continue. Being a project manager in this situation has developed a lot of my skills from time management, budgeting and planning. I’ve become more responsible leading people and my skills have massively improved working in a team. It’s been a wonderful year. The amount of people I’ve met, spaces I’ve visited, doors that have opened. The practical impact was massive. Without the funding, the majority of the things I’ve done wouldn’t have come to fruition. It’s given me belief in myself. Blagrave funding me is like they believe in me. I feel very confident and I feel like it’s important for me to continue the work. It’s sprung life into me.”

Ibrahim is making plans to engage more local young people in regular allotment workshops and hopes to expand the project by offering residential opportunities in rural areas for young people from urban areas.

“In May 2022, I participated in a residential in Wales as part of a project called Growing Off Grid, organised by KORI and Feedback Global. I was connected by the organisation I’m a member of, Forefront. I did activities like hiking and visiting a waterfall. I was really inspired by the experience. We did weekly workshops leading up to it, getting to know the people involved and learning about food systems. During that time, we were told about Challenge and Change and that’s when I started to think about applying to create my project. We learned about indigenous ways of farming and visited the Centre for Alternative Technology in Machynlleth. We climbed a mountain and went on a journey together, starting from the bottom and going through the struggle together to reach the top. I couldn’t put that experience into words. Pictures don’t do it justice. You feel on top of the world. It’s only right that I give the same opportunity to young people like myself.

At the end of the day, I’m from northwest London, that’s important. My friends would tell you that I’m someone who loves their family, their community, where they’re from. I take pride in that and I try to look after the people that grew up around me. That’s something I’ll take anywhere in life, wherever I go. I’ll always remember where I came from.”

—

If you’d like to connect with Ibrahim, you can do so by following him on instagram @glizzackk and by email ibrahimjsalah@gmail.com.

–

The Challenge and Change Fund is designed by young changemakers for young changemakers. It funds young people directly, supporting them to create the change they want to see. It prioritises young people who are emergent and have lived experience of the injustices they are trying to change, supporting youth led collectives, social enterprises and CICs across England. You can read more about Challenge and Change here.