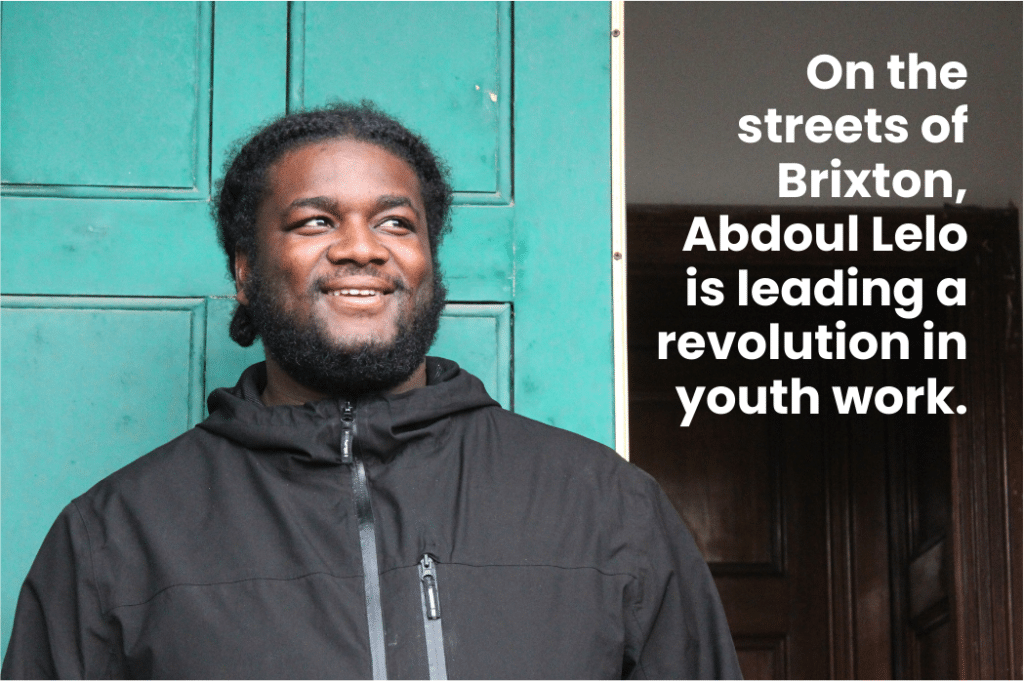

With support from the Challenge and Change fund, Abdoul has scaled up his pioneering approach to youth work by creating Shou’Been, a vital new youth space in Brixton, the beating heart of the London Borough of Lambeth.

Abdoul Lelo worked with young people long before he became a professional Youth Worker.

“Coming from where I’m from in Congo, I learned about how a village actually is,” he says. “It takes a village to raise a child, which is not really practised in other places. When I was living there, everyone was looking out for me, looking out for the young people living in the community. I moved to Angola and it was similar. My neighbour’s dad taught me how to ride a bike.”

When Abdoul and his family moved to England, he noticed a cultural difference between his experience of childhood and how children were treated in his new community.

“People were happy that we moved there because we were the ones knocking on people’s doors to say ‘come play football,’’’ he says. “We were trying to bring that community that we had in Congo here. It worked. The neighbours started to bring around bouncy castles and everyone started cooking food and sharing food with each other.”

Abdoul’s experience of the school system in England was similarly illuminating, and has greatly informed his practice as a Youth Worker today.

“Young people feel like they’re in prison, not going to school. They feel like they’re going to prison. But because they’re running away from problems at home, it’s therapy for them. Imagine that. The reality is that some people actually go to prison because they don’t have a home, they don’t have free food. They feel like they’re being taken care of by the prison system better than when they were outside in society. It’s the same in school.”

Abdoul observed the connection between poor treatment of children and poor outcomes in and outside of school. He noticed, in particular, that adults and caregivers in his community prioritised educational attainment over the emotional wellbeing of the children he knew.

“Try to understand why a young person will be doing certain things when their primary caregiver is just a person who provides them with a house, not even a home, and then they go outside and their friends are actually playing the role of the person who shows them affection and gives them time.”

In response, Abdoul positioned himself over a number of years as an alternative figure for young people to draw support from in Brixton; a young person with the lived experience and tools to successfully guide young people down more positive pathways. More than this, Abdoul positioned himself between young people and authority figures, including elders, shop owners and the police and, to this day, acts as an intermediary during moments of tension within the community.

“I’m trying to be the change that I want to see. I don’t want to just talk about it. I don’t want to wait for the police to do it. I want to be part of the change.”

That Abdoul is well regarded in Brixton cannot be overstated. On a five minute walk through the high street, he is stopped by at least a dozen people of all ages for a hug, a dance, a fistbump, a chat, a handshake.

“Everyone gravitates towards Brixton,” says Abdoul. “There’s an energy in Brixton that everyone loves. When you come here, you feel like you’re part of the community. Although there’s lots of things to do in Brixton, a lot of that is not directed towards kids, so some young people go a little bit over the top and those are the ones that companies like Morleys, Creams, McDonalds and KFC struggle with. They struggle to understand that these young people may be deemed as ‘hard-to-reach’ in schools so they show that everywhere they go.”

For many of these high street businesses, Abdoul has become the first point of contact when young people are being disruptive.

“When shops are about to call the police because the young people are causing havoc, I say ‘nah, don’t. Call me instead and I’ll make sure that they’re good. I’ll make sure they’re not disrupting or nothing. When they come in here, they’re eating and then they’re leaving, don’t worry.’”

Some young people do, nonetheless, come into contact with the police despite the progress Abdoul has made in minimising these types of interactions. As a result, he has adopted an approach that’s considered controversial by some in an environment where the relationship between the police and the public can be hostile: he tries to maintain a positive relationship with a select few police officers who he trusts because of their work to challenge colleagues who “aren’t doing the best for the community- the ones that are involved in the negativity.”

Historically, Brixton has been the site of protracted discrimination and violence by police towards Black people, including an aggressively administered stop and search policy that continues to this day. Abdoul believes that forming these kinds of relationships is integral in building a consent-based policing model in which the community is responsible for solving issues before police become involved.

“The police are always going to be policing, but I’d rather they were policing with our consent,” explains Abdoul. “And when we police our neighbourhoods ourselves, then the police that are trying to come and help can do a better job because they know that they’ve got the community’s support. I want to make sure my community is good. I’m trying to be the change that I want to see. I don’t want to just talk about it. I don’t want to wait for the police to do it. I want to be part of the change.”

“The goal is to put systems in place which will keep young people safe from gang culture as well as introducing them to people who can help with employability and occupy their time.”

“The goal is to put systems in place which will keep young people safe from gang culture as well as introducing them to people who can help with employability and occupy their time.”

For years, Abdoul did this work informally until local youth organisations took notice and employed him as a paid Youth Worker. In Angell Town, on the northern border of Brixton, Aboul regularly opens up a facility for young people called CHIPS, where he is a Youth Worker, and he often takes young people to a larger facility, the Marcus Lipton Youth Club, for sports and other recreational activities. Abdoul is also a Youth Worker for Spiral, which has supported him to gain new youth work qualifications, and works with children at a local school to understand their career options and enrol for college and work experience placements. He works a fourth job: as a Youth Leader for Ecosystem Coldharbour, through which he is able to continue delivering street outreach.

“You’ll find me on a main road trying to bridge the gap between young people and organisations,” he says of a typical day at work. “That’s what I’ve been doing for free in my own time but now there’s people that appreciate what I do and they show it, hence why they’ve actually brought me into their organisations.”

With support from the Challenge and Change Fund, Abdoul created a new project to end youth violence, Shou’Been, which runs monthly events on estates throughout Lambeth that are carefully designed to reduce interactions between gangs and decrease the long-term chance of young people participating in activities that could harm them or the community.

To this end, Abdoul schedules events to run simultaneously across youth violence hotspots in Lambeth so that opposing gangs will not be at the same event. At these gatherings, young people of different ages can access information about local opportunities and networks through which they can access support, including the other youth organisations at which Abdoul works. He co-designs and delivers the events with local young people who gain valuable work experience from event organisers, musicians and artists.

Additionally, Abdoul has enabled trusted elders to acquire a Security Industry Authority accreditation while overseeing safety and security at these events. He believes that increasing the community’s capacity to keep itself safe will reduce the risk of police imposing themselves upon community events.

“The goal is to put systems in place which will keep young people safe from gang culture as well as introducing them to people who can help with employability and occupy their time. Thanks to the Challenge and Change Fund, that was fulfilled. The Fund could see the passion and just wanted to help. Those are the people I want to work with. I appreciate Blagrave. Providing young people with that space is the best thing I’ve ever done.”

In August 2023, Abdoul registered a CIC, OneWithTheVillage, of which Shou’Been is now the main project. OneWithTheVillage formalises Abdoul’s role as a bridge between youth services and young people in need of safe spaces, work opportunities and positive adult connections.

“OneWithTheVillage is driven by the belief that a thriving community is built on unity and collaboration,” says Abdoul. “Our ethos is inspired by and emulates growing up in a village and witnessing the interconnectedness and shared ambition of its members in raising young people. Our common goal as a community is to empower and support young individuals in achieving their aspirations and reaching new heights in their chosen careers.

Our approach involves extensive outreach throughout London and Lambeth, beginning within the local community where we have already built rapport with young individuals. As a team, we are committed to reintegrating young people into education and training by connecting them with appropriate youth services that provide relevant support. We facilitate connections with organisations that assist in CV writing, offer free tuition in youth facilities, and provide access to wellbeing and support services. Our aim is to acquaint young individuals with youth services they may not yet be familiar with or have yet to engage with.”

“Sometimes I feel like we can be hard to reach. Kids are not hard to reach. We’re just not reaching them the way they want us to.”

The knack is this, according to Abdoul: if you take away something that young people perceive as fun, you need to replace it with something better.

“One thing that I don’t want to be is another authority figure,” he says. “They’ve got too much of that in school, at home and from different people, especially police. When I go to them, I try to make them understand that the reason why I’m here is the same reason why I’ll be at your Mum’s business or your Dad’s business doing the same thing. I don’t want no one ruining anyone’s business and giving them an alternative is a big thing. I can’t just take away your fun and not give you somewhere else to go.”

By hosting Shou’Been at local community spaces like CHIPS, Abdoul now has a physical space to which he can direct young people that he’s diverted from a potentially harmful activity. For example, he often deals with incidents of young people stealing from each other by offering them something different, including access to activities at CHIPS and Shou’Been.

“It’s because they’re seeing what their friends have and they don’t have it and so we get to a point where they’ll give back the stuff they’ve stolen and then I’ll get them something else, something from a shop. They don’t feel like I violated them because I’ve told them why stealing isn’t good and I’ve also given them something just so they don’t feel like ‘he’s taken the mick out of me or he’s making me look soft and all of that.’ No, it’s not about that. I just try to make them know that you don’t need to steal. You don’t know what this other child’s parents went through to even be able to get that for him”.

Abdoul can already see the impact of his work. These days, he says, if staff at a local shop video-call him so he can talk to young people who they believe are causing problems, the young people leave immediately out of respect for him. More and more, these children ask Abdoul to open up CHIPS so they have something else to do.

“We’re talking about kids that are deemed as ‘hard to reach’ and sometimes I feel like we can be hard to reach. They’re not hard to reach, we’re just not reaching them the way they want us to. So it works. When I go McDonalds and the young people see me they’re like, ‘we’re not making noise!’”

“I want young people to feel like it’s their responsibility to help those they can’t see.”

By every measure, Abdoul’s approach is working. Despite this, he has endured substantial backlash including extreme physical violence. He has been stabbed several times and sustained a severe head injury when he was attacked with a hammer. Though the community is hugely expressive in its support for Abdoul, he remains acutely aware of his safety even in busy public places in Lambeth. Perhaps this explains why Abdoul often thinks about his legacy, despite being so young.

“These young people here, I’ll be glad to hand over certain things but I can’t just give it to them without empowering them with the tools to be able to use it. I don’t want to just leave this world without leaving something for the people I love and I’ve seen a lot of my friends do that. A lot of my friends have passed and I left them when we were sixteen, fifteen and eighteen, so some of my friends are still eighteen, you understand? They didn’t leave anything in this world.”

One day, when he is ready to hand over his work to the next generation, Abdoul plans to build two orphanages in Congo and Nigeria in honour of his grandmother, who was an orphan. He hopes that young people in Lambeth will play a role.

“I want young people to feel like it’s their responsibility to help those they can’t see and to make them understand that we have it alright and there’s some people that don’t. I don’t know how many young people have actually seen another country. Hopefully I’ll be rewarded even when I’m not in this world anymore.

For now, I’m building a world where everyone understands the system that’s in place, where traumas come from, facing trauma, understanding your triggers before going out there and actually working with young people who also have their own traumas. I’m creating a space where parents can come and actually talk to their kids and explain that there was no manual that was given to them. There is a root to every pain and every stress. If we address it, we can move on.”

Despite the nature of his work, Abdoul retains a joy in serving young people.

“People say to me, ‘don’t you get tired of saying hello to people?’ Do you know what? I’m an extrovert. Those that benefit from me being around them, I benefit from it more than them and I enjoy it. I feel like every person that comes and says hello to me charges my battery to the fullest.”

–

The Challenge and Change Fund is designed by young changemakers for young changemakers. It funds young people directly, supporting them to create the change they want to see. It prioritises young people who are emergent and have lived experience of the injustices they are trying to change, supporting youth led collectives, social enterprises and CICs across England. You can read more about Challenge and Change here.

“The goal is to put systems in place which will keep young people safe from gang culture as well as introducing them to people who can help with employability and occupy their time.”

“The goal is to put systems in place which will keep young people safe from gang culture as well as introducing them to people who can help with employability and occupy their time.”