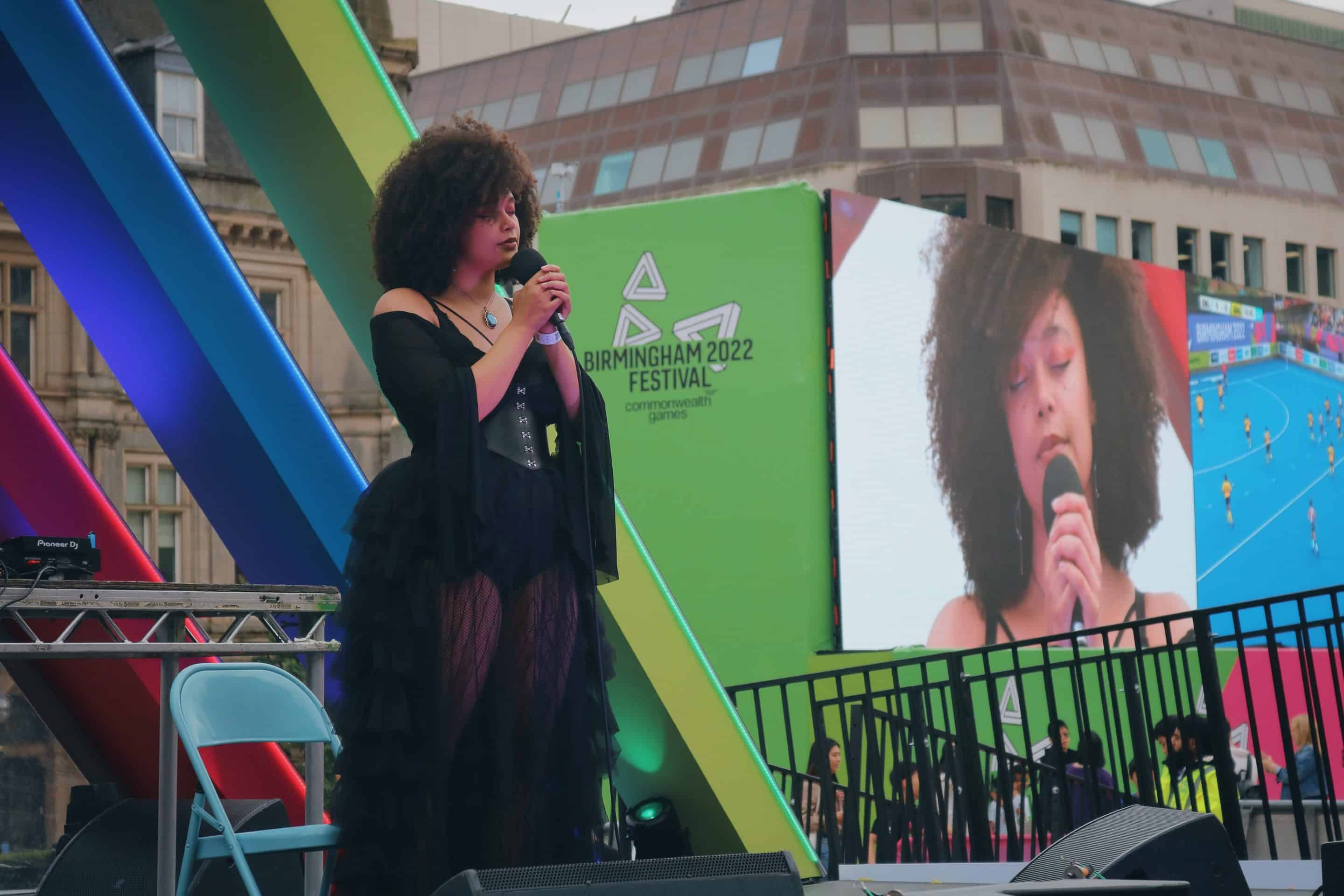

For founders Elle Chante and Katie (Tom) Walters, the idea behind Radical Body Arts came from a simple, relentless truth: the arts world was not built for them.

As disabled artists, they knew firsthand how inaccessible and exclusionary the arts world could be. They had experienced exhaustion and frustration trying to perform in spaces not built for them. So they decided to take matters into their own hands.

As disabled artists, they knew firsthand how inaccessible and exclusionary the arts world could be. They had experienced exhaustion and frustration trying to perform in spaces not built for them. So they decided to take matters into their own hands.

Founded in 2018, Radical Body Arts had a clear mission to make the arts more accessible and sustainable for disabled people. That meant rethinking everything, from what a commission could look like, to how performances were shared, to who gets to create and where. “Most programmes expect the artist to go to them,” Elle explains. “We take the opportunity to the artists.”

Their model is grounded in understanding what artists with disabilities need. “We’re a very small team of disabled artists ourselves, and so we understand where some of the barriers are.” Elle explains.

They run online scratch nights and digital commissions, often sending camera kits directly to artists who struggle to leave their homes. The work is shared through livestreams and video, making space for those often excluded from traditional venues. “Some of the projects are directly working with the artists — funding them through commissions and creating those opportunities,” Elle says. “But even just encouraging more of those commissions to be seen helps show the world, and the industry, what that art looks like. It proves this work can be seen, shown, and consumed — even if the venues hosting these opportunities are inaccessible to the artists.”

Early on, Radical Body Arts spent time experimenting about what worked for them as an organisation and what worked for the artist community they wanted to serve.

“We did a lot of work testing out different ways of working in the arts sector before arriving at where we are now. We went from doing more in-person work, to hosting everything online, to research that provides helpful information to lots of organisations and people. Now we have a much more rounded view of the kind of work we can do, what’s sustainable for us, and what’s genuinely useful to the sector.”

As their work developed, so did the need for systemic change. So, in 2025, Radical Body Arts launched the Disability Data Drive. With over 250 respondents, it revealed the extent of exclusion of disabled artists in the sector: nearly 89% had questioned their ability to work in the arts because of access needs, while more than half had turned down jobs because covering access costs would make the work financially unviable.

The survey was also a response to the funding landscape. “Making something accessible and safe isn’t always understood by funders. If you’re working with disabled people, you might not want ten participants, you might want five, and to be able to safeguard them well. But the funding world doesn’t always lend itself to that. It’s all about: how many people are you reaching? What does it cost? Is it value for money? That kind of thinking doesn’t really serve the disabled community well. So we felt like we had to prove, on paper, that it’s important.”

Support from the Pathways Fund helped Radical Body Arts shift from survival mode into strategic growth. “To be honest, I don’t think the work would’ve been possible without it,” Elle says. “Access has costs. Training is expensive. And when you’ve got limited time and energy, voluntary work becomes impossible. The Pathways Fund meant we could hire a team, plan properly, and keep going.”

The flexibility Blagrave offered enabled them to rethink delivery timelines, restructure roles, and care for themselves and their collaborators. “The Wellbeing Grant was helpful,” Elle notes. “But honestly, just not being punished for moving at a different pace to organisations that are non-disabled was really appreciated.”

Even funding itself can feel inaccessible. “You often need to be a charity to apply,” Elle explains. “But we don’t have the capacity. We can’t take on all that paperwork, or meet all the criteria. That locks so many of us out.”

Her message to funders is clear:

“If you don’t fund people who’ve never had funding before, then you’re just going to keep regurgitating the same stuff.

When disabled people can’t access creative spaces, then creative spaces miss out — on experience, on perspective, on art. Art is meant to express experience, and when disabled artists are excluded, the whole sector loses out. It’s a big L for the arts.”